Rules Management

Overview

Before proceeding with the other transactions in ETRACS, it is important first to discuss Rules. One of the components that make ETRACS special and the only one of its kind is the use of Business Rules to customize the system to fit the LGU’s requirements. The business rules are executed in a special software called a Rule Engine. Some of the application of business rules in ETRACS are as follows:

Calculating taxes and fees in business assessments

Determining requirements in business

Compute Billing and calculating penalties

Customization of workflow

Before when one wants to customize the system they must have a ready programmer who can edit the code. This is time consuming, error-prone and very difficult to maintain. In ETRACS, customization is done by authoring of rules through an intuitive user interface. Before rules can be created however, the rule author must know the behavior of rules and its effects. Rules can be simple or complex depending on the requirements of the LGU. Rule authoring requires logic reasoning and those will author rules must know how to interpret the rules and can translate or express it using the rules interface. Ideally, rules should be done by the domain expert, i.e. the one knowledgeable about the ordinances for example. However rule authoring requires special computer operation, that’s why it is recommended that rule authoring be assigned to an IT personnel with approval by the domain expert. If the domain expert is computer savvy enough, then they could also do it themselves.

What are Rules

A rule engine is a special software that separates business logic from application code and classified as an expert system, a branch of artificial intelligence that aids in the decision making process. The rules resemble a language that can be clearly understood by a normal business person. The rules are relatively easy to understand and is intuitive. It is composed of two parts - a Condition and a Consequence or Action. Pieces of information called Facts are evaluated in the Condition part, known as Constraints, such that if all constraints are true, the related action will execute. The following is a pseudo example of a rule construct:

when (condition)

Application (type is “NEW” )

Line of Business (classification is “Manufacturer”)

CAPITAL is provided for said Line of Business

then (consequence or action)

Add “BUSINESS TAX” using formula: “CAPITAL \* 0.30 \* 0.01” for the

said line of business

This piece of rule is an excerpt from the Business Assessment Rules. In simple terms, this means if an application is for a new business, and has a line of business which is classified as a manufacturer and the capital is provided for this line of business, then we add a business tax where amount is equal to CAPITAL * 0.30 * 0.01 and must be applied per line of business.

In business applications, there are sometimes more than one line of business for a business. For example there is an application that has two lines of business, one manufacturer and the other retailer, only the manufacturer in this case will be computed for business tax because the retailer does not match the condition above. For another example, if the application being evaluated is for a Renewal application, the rule above will not fire because it explicitly states it is applied only for New. So in other words, for a rule to execute, all constraints in the condition must evaluate to true. If even one is not true, the rule will not execute.

By creating many rules, the desired effect will be completed. There could be many rules or few rules depending on the area being addressed. Rule engines are quite powerful because it is designed to execute very fast no matter how many there are and that makes it special. However, one needs to be careful because sometimes there are overlapping rules and the rule author might have difficulty tracing and correcting these rules to eliminate the side effects.

Rule Execution

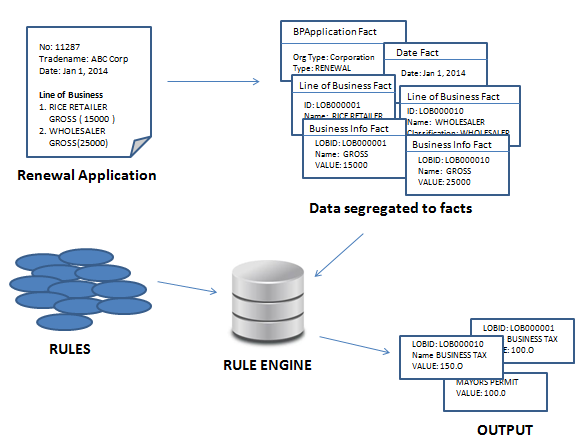

Rules operate on data called Facts. A fact is a structured holder of data that is evaluated by the rule engine. When authoring rules, we specify which facts we want to evaluate. Data from the application inputted by the user are sent to the server. Before data is processed by the rule engine, it is first segregated into facts which becomes the input data for the rule engine. The engine searches for rules that match the given facts and executes those that match to produce an output.

Figure 20 Rule Execution

Rule Groups and Salience

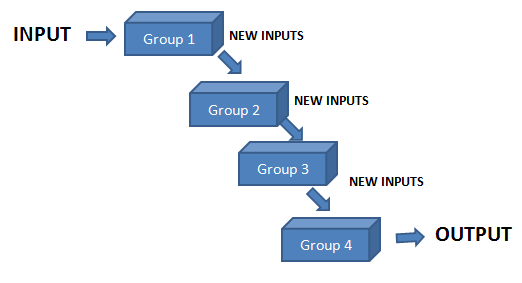

In order to avoid possible complex non-terminating rules or “endless loops”, the rule groups are provided. Rule groups are like compartments wherein the input is processed then output is generated in a straight chaining manner. The output of one chain becomes the input of the next chain so on and so forth until we get to the last before it ends processing.

Salience refers to the order in which rules executes. If there are two rules in the same rule group, the one with a higher salience will always execute first. The general behavior of ETRACS is overriding, so the lower salience or the last rule executed will always prevail. So if you want some rule to execute in general, i.e. one that might be applied to all, make the salience a very high number. If you want more specific, make salience a lower value. To understand this further, refer to the application of rules in the business and real property sections.